“The pain, the body, the city, the country. Kahlo. Frida, the art of Frida Kahlo.”

Never is the phrase ‘life imitates art’ more applicable than in reference to the life and work of Frida Kahlo.

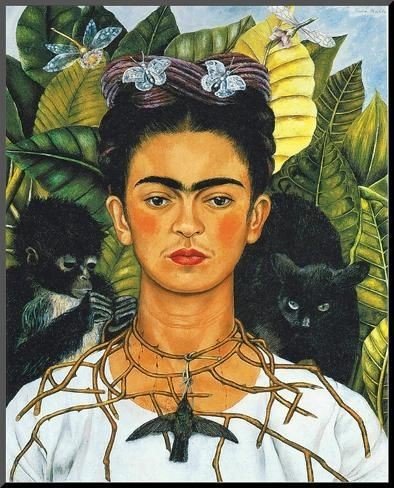

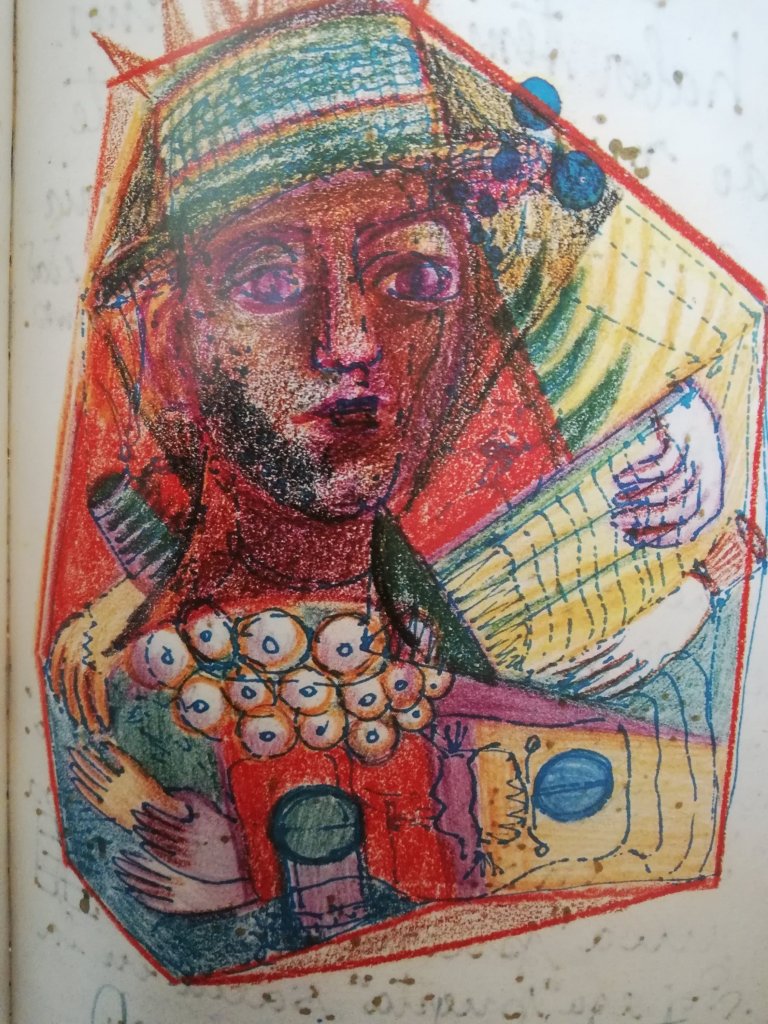

Considered a modernist surrealist, her most famous works depict alarming, jarring images spurned from her constant daily battles with physical pain. Her tortured narrative. Yet, initially when one hears her name, images of bright colours and tropical flowers often spring to mind. Almost Aztec-inspired, and jovial in their nature. A fusion of bold vibrancy and nightmarish acid trip elements. Intriguing, no?

So where did it all begin?

To say Frida was no stranger to pain would be more than something of a mild understatement. This woman’s body literally held out for as long as it could (all of forty-seven years) which, given what it went through, actually wasn’t bad.

Frida famously described her body as tortured and cursed; betraying her on the daily, and that it was actively failing. To those outside of Frida’s personal orbit, this might be considered a classic overreaction from a textbook hypochondriac. Not the case. This was actually exactly what was happening.

It all kicked off (bad pun intended) when Frida contracted polio at aged six, which caused a growth defect in one of her legs, resulting in a ‘shrivelled’ appearance, as the leg in question was shorter and thinner than the other, thus leaving her with a lifelong limp. In writer Carlos Fuentes’ biography he described her as going from a beautiful, happy child; renowned for her ribbons and bows and adorable hairdo, to then being considered a circus freak in the eyes of her young peers; who would mercilessly bully her at school, dubbing her Frida pata de palo, which translates to Frida the Peg-leg. She would go on to spend the rest of her life self-conscious of this defect and it would be one of the reasons behind her trademark long, billowing skirts.

There is a general respite in physical torment for almost twelve years, which would then come crashing down with absolute gusto in 1925, when at aged eighteen, whilst returning home from school one afternoon, the wooden bus she was riding on collided with a streetcar on a busy street in Mexico City. The injuries she sustained from this accident were almost unimaginable. Here’s the general recorded low-down: a broken spinal column, a broken collarbone, four broken ribs, eleven different fractures in her disfigured leg, at least two dislocated vertebrae, and a crushed foot. As if this wasn’t bad enough, a bus handrail had become detached and had impaled her through her lower back, exiting out of her vagina, shattering her pelvis in the process. Ouch…

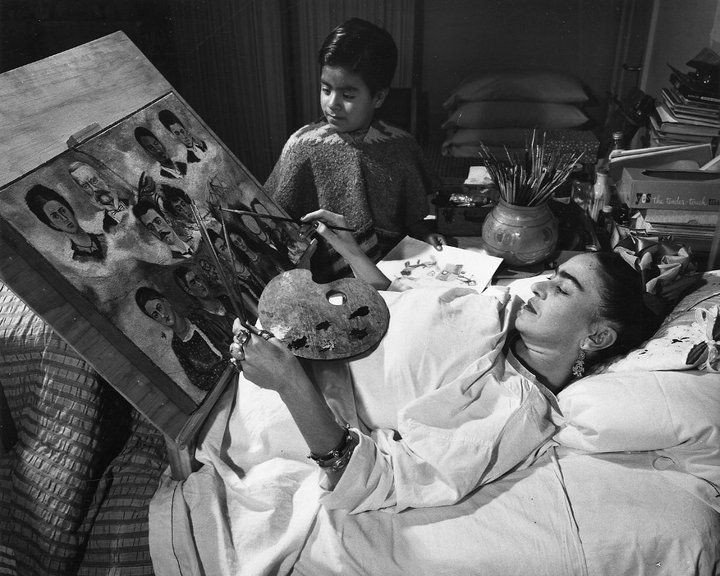

Naturally, Frida was out of action for a good while. Her recovery entailed months and months of operations, bed-rest, physiotherapy, and body-casts and corsets designed to re-join her broken body, with materials ranging from typical plaster to stainless steel. In her lifetime, she had a whopping THIRTY-TWO operations. It’s now a bit easier to understand why Frida didn’t speak too highly of her body.

In theory she survived this accident, but in a way she also didn’t. The impact of her injuries would rear its ugly head in every corner of her life, and marked the beginning of the slow, lengthy descent towards her death. With the medical care of that time period being not quite what it is today, her body just couldn’t restore itself. As she got older she was in and out of hospital having gangrened fingers and toes amputated, and eventually her leg at the knee, forcing her to spend her few remaining years wheelchair-bound. Her extensive reliance on alcohol as a way of self-medicating and managing her pain obviously had counterproductive results on her body’s ability to heal and function. It’s said that she pre-empted her passing, and in the weeks running up to her death she jokingly referred to herself as a ‘walking corpse’…

Bet she was a hoot at parties… (she actually was but we’ll get to that later.)

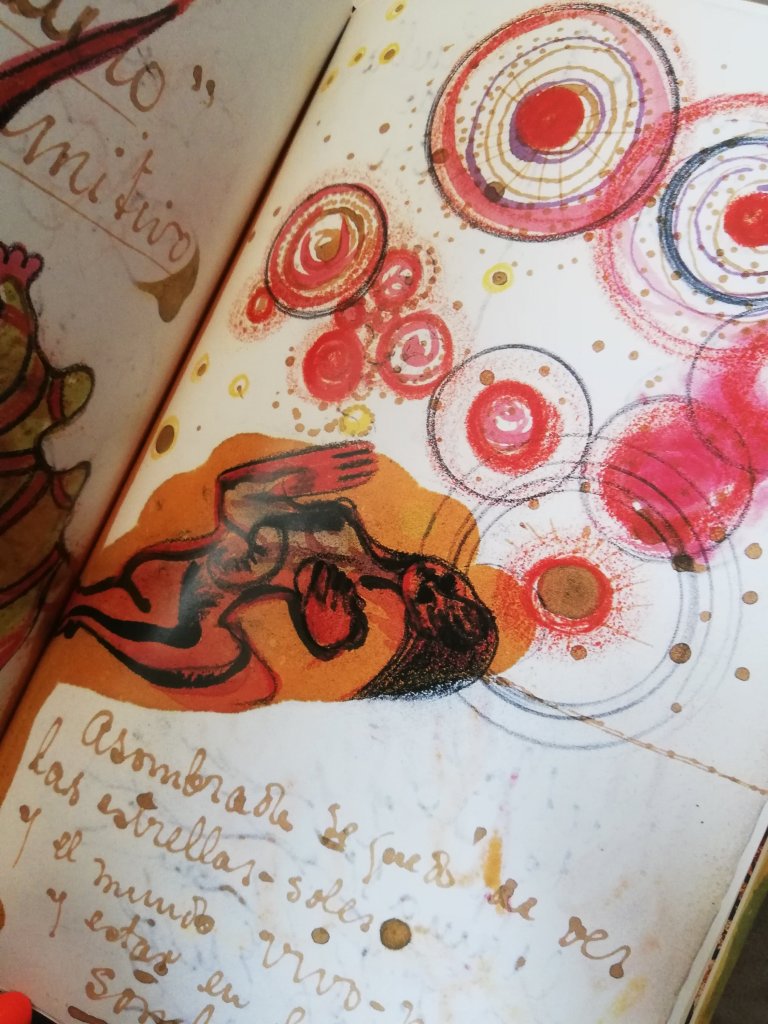

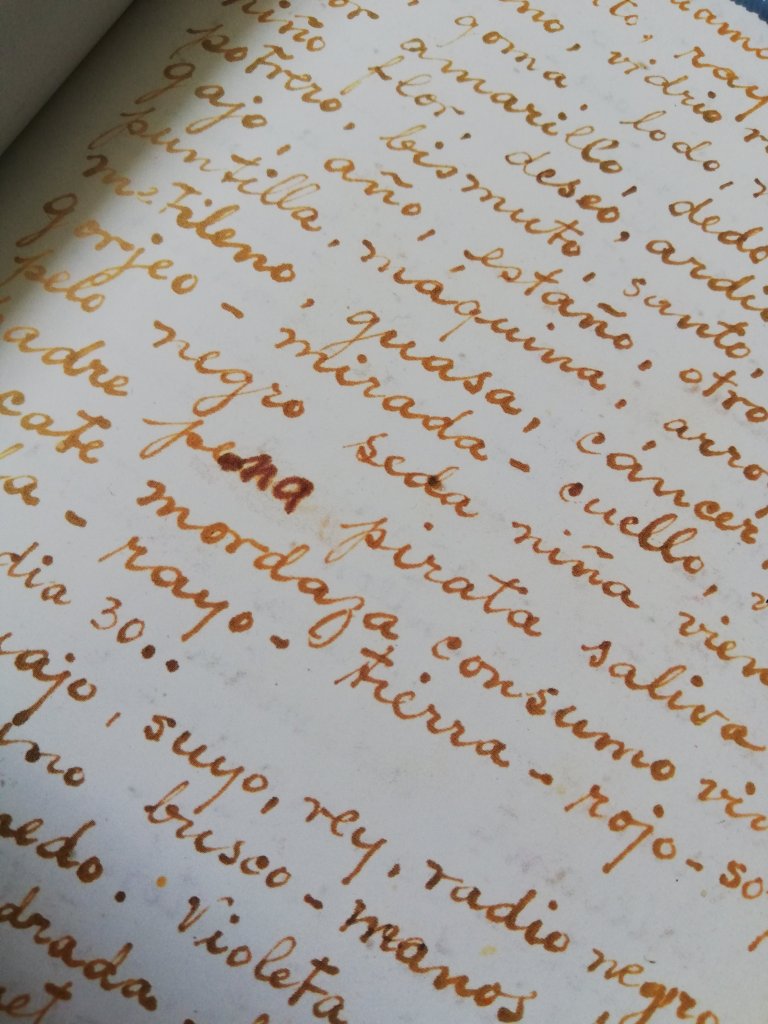

“I am the subject I know best.”

The plus-side to all of this unholy mess – the silver lining – was that it would trigger her love of drawing and painting, and would be the carving of her artistic legacy. Whilst bed-ridden, with her movement exclusively limited to her hands and arms, she would wile away the hours by turning her white plaster body-cast into a mural of beautiful flowers, before moving on to more serious artistic endeavours, in which her dad would then rig up drawing boards with canvases attached from her bedframe so she could paint whilst lying down. The ramifications of both her injuries and the time it took to generally recover had shattered her dream of becoming a doctor, but ignited her love of art. Definitely a ‘no shit’ moment to the classic ‘everything happens for a reason’ theory…

She became an established artist and a household name in her own right, with her paintings being engines of her cathartic release. A lot of her well-known pieces are self-portraits which depict the alarming effects of her physical (and often emotional) state.

The damage from the handrail had rendered her reproductive system only semi-functional at best, which sparked a continual crisis within her about childbearing and would it be worth the potential physical and emotional risks. All of this is very evident in her self-portraits.

Speaker of Pain

So, it’s fairly easy for us to empathise with Frida’s use of art to tell her story and to exercise her various physical demons, but Frida was also very politically-motivated and only too aware of the events of the world. Her childhood years from aged three to thirteen were dominated by the Mexican Revolution, which saw over one million of her people slaughtered. She also lived through both of the World Wars, with her ancestry going back to German and Hungarian Jewish origin, and so was naturally rattled by Hitler and Stalinism. She was a lifelong member of the Communist party, and so the Arms Race and McCarthyism that rumbled along in the background of her later years played a part in her anxiety.

She also notably allowed for some dark humour to creep into her work. At some point, she was commissioned to paint a tribute portrait of young Hollywood starlet who had committed suicide by jumping off of a building – and her tribute would be exactly that. An image of this woman sailing out of the window and crashing to the ground…

It’s not known as to whether the painting was some rather dark and rather tasteless joke, or whether Frida was just moved by this woman’s dramatic exit and wanted recreate her final journey. Latino culture famously celebrates death as a beginning and not something to be mourned, so the thought-process behind it was a matter of some debate. Either way, the commissioner reportedly nearly fainted at the sight of it. Individuals much-less concerned by propriety, however, thought it was hilarious. Nevertheless, it was a piece of art that wouldn’t be forgotten in a hurry.

The Elephant and the Dove

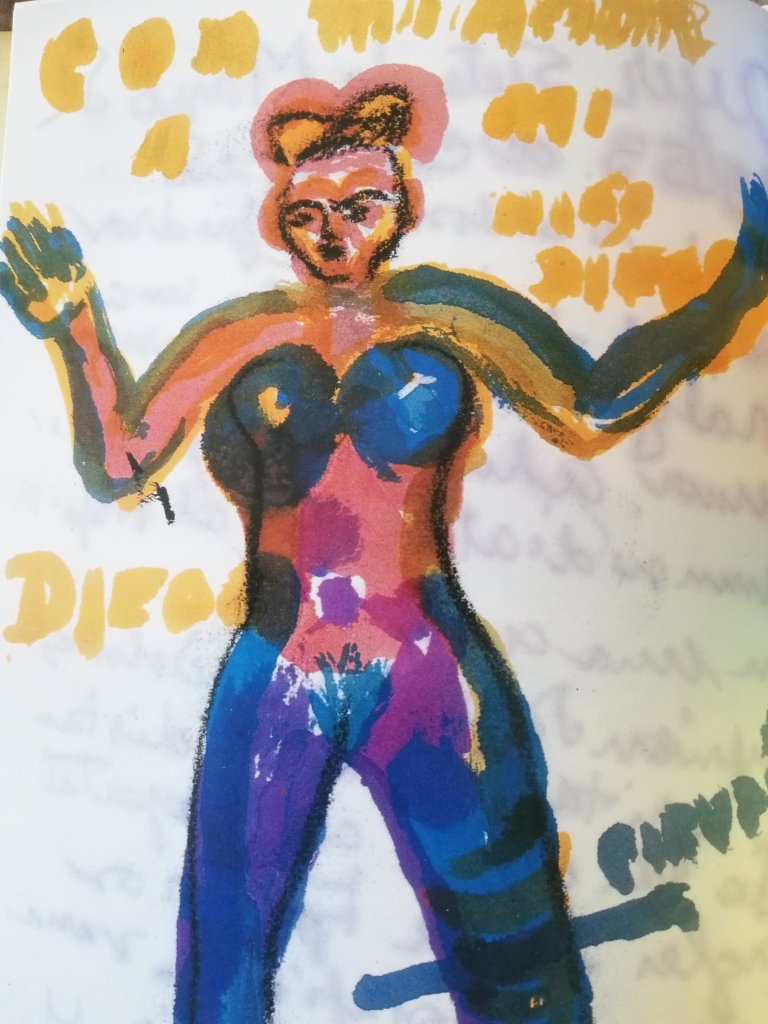

Frida met and fell in love with the famous Mexican mural painter, Diego Rivera. They married and then divorced and then married again (as you do) and remained married until her death in 1954. Though the relationship was somewhat volatile and fraught with infidelities from both parties, as well as antagonised by her physical pain, his workaholic nature and lack of sensitivity, and then temporarily fractured by a very aggressive miscarriage that had hospitalised Frida for two weeks, thus triggering a months-long depression, theirs was a coupling that defied a lot of odds. They were mutually supportive and unquestioning of each other’s artistry, abundant in affection, physically and politically compatible, and simply loved each other in a way a Brontë sister might have written about. Not quite #couplegoals, but not far off.

Those who have seen pictures of them together will understand the meaning behind the ‘elephant and the dove’ reference, which was initially coined by Frida’s folks upon hearing the news of their marital ambitions. Let’s just say that Diego wasn’t beauty pageant fodder. He was built like a brick shit-house and had a face for radio, bless him.

So What Makes Frida a Badass?

I think the more relevant question is what doesn’t make her a badass?!

It’s acceptable to suggest that Frida’s work is an acquired taste, and not necessarily the type of art you’d like to see first thing in the morning hanging on your bedroom wall. But she was brash, unique and unapologetic in her artistry and she didn’t give a foof what anyone thought of her. She painted what the hell she felt like, wore what the hell she felt like, drank what the hell she felt like (and that girl LOVED her tequila), fucked who the hell she felt like (I don’t condone adultery, of course, but it’s more a context sort of thang), swore like a sailor, and could fiesta ‘til the cows came home.

But what I really like and what is a continual theme within my writing, is women (particularly women from yesteryear) who aren’t afraid to stand within their power, and have no issue defying expectations and saying ‘you know what? Sod you. I’m doing life my way or the highway.’ It’s not easy – even today – to have that attitude and it sure as hell couldn’t have been easy for a woman in 1920s Mexico living under a fascist dictatorship and within a tortured body that straight-up just wouldn’t play ball. So for that I say good on ‘er! Vive la Frida!

[All words are my own and are subject to copyright, with the exception of the opening quote, which is from writer Carlos Fuentes. Information is sourced from both him and essayist Sarah M. Lowe. Illustrations by Frida courtesy of La Vaca Independientes. All other images are referenced above. No copyright infringement.]